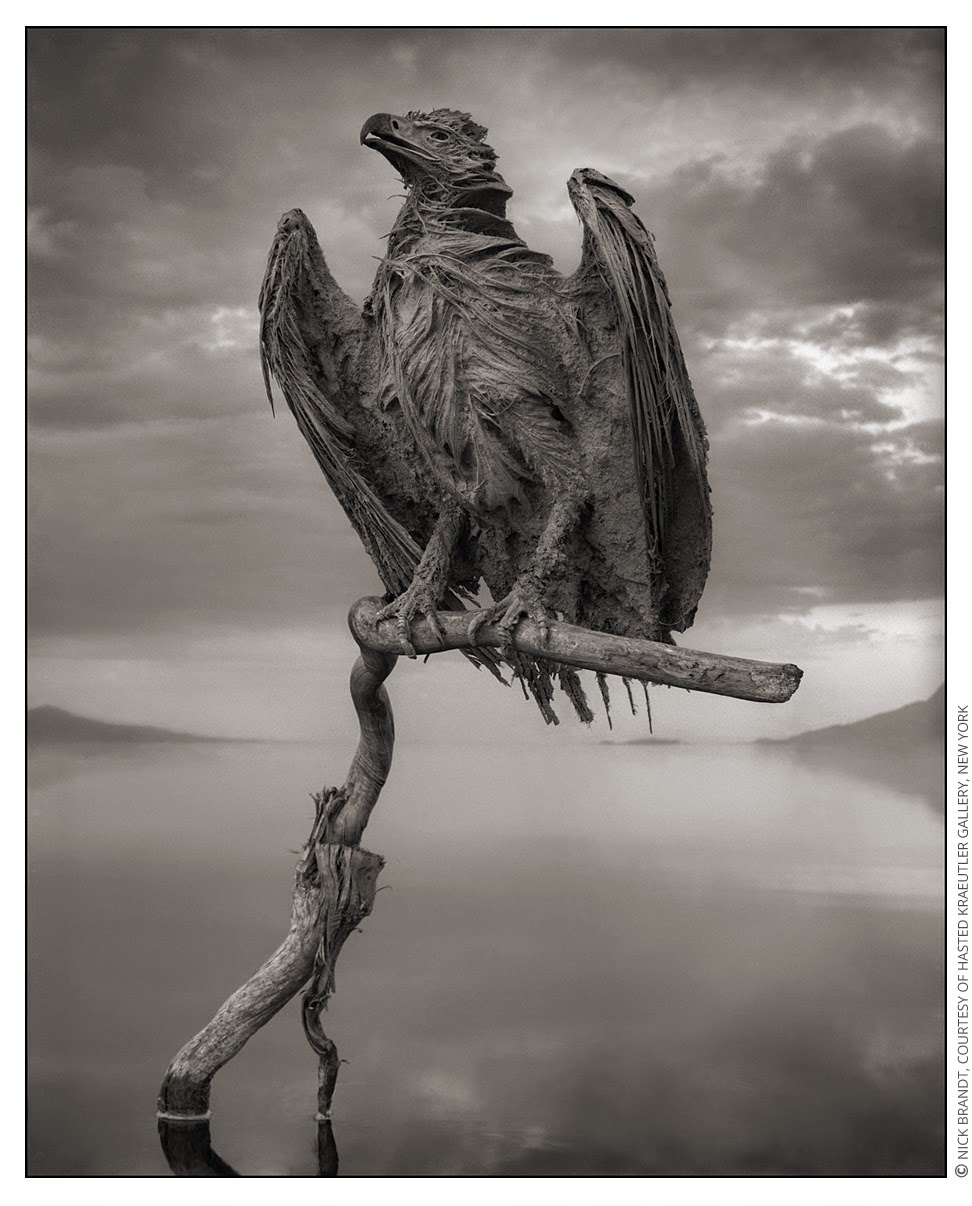

To take a portrait of an animal alive again in death, in the place where it lived and died. The portrait of an animal that I would never have been able to get close enough to otherwise. This was part of what obsessed me when I first unexpectedly found petrified birds and bats washed up along the shoreline of Lake Natron in Tanzania.

I visited the lake whilst traveling through one the more stark areas of East Africa taking photos for the last book, Across The Ravaged Land, in my trilogy. It was dry season, so the waterline had receded revealing these petrified creatures along the shoreline. I thought they were extraordinary - every last tiny detail perfectly preserved down to the tip of a bat's tongue, the minute hairs on his face.

Each day, me, my guide, and a few local Maasai would walk up and down the lake's shoreline, scouring for birds and bats. It was like a morbid treasure hunt, with the entire fish eagle being the most surprising and revelatory find. His outspread wings, as if opening them to dry them in the sun, were fixed in exactly that position when he died.

No-one knows for certain exactly how the animals die, but it appears that the extreme reflective nature of the lake’s surface confuses them, just like a plate glass window, causing them to crash into the lake. The water has an extremely high soda content, so high that it would strip the ink off my Kodak film boxes within a few seconds. The soda and salt causes the creatures to petrify, perfectly preserved, as they dry. (I have referred to the creatures as calcified in previous titles/descriptions, but “petrified” is the correct description).

We have found entire flocks of 100 dead small finches washed up on shore in a 50 yard stretch of shoreline. So clearly, they all died at once. Which suggests that the notion that they accidentally all flew into the glassy reflective surface of the water is a very plausible theory. All in all, not a great-sounding way to die.

All the creatures are rock hard when found, but are not stone, as reported in many articles. You cannot turn their heads, manipulate their wings, etc.

I took these creatures as I found them on the shoreline, and then placed them in ‘living’ positions, bringing them back to ‘life’, as it were. Reanimated, alive again in death.

In the instance of the fish eagle, we placed him on a strong branch pushed into the shallow water of Lake Natron - photographing his portrait far closer than I ever could if he were living.

Shot as always on medium format black and white film, the photograph is published in “Across The Ravaged Land”, available on Amazon.com (SIGNED copies available from www.photoeye.com).